- Home

- Pierre Louys

The Woman and the Puppet Page 9

The Woman and the Puppet Read online

Page 9

“It’s my guitar, and I’ll play it for whoever I like!”

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

HOW MATEO RECEIVED A VISIT, AND WHAT ENSUED

If I didn’t kill myself on returning home, it must have been because over and above my tortured existence an anger yet more powerful sustained and counselled me.

Incapable of sleeping, I didn’t even go to bed. Daybreak found me on my feet, in this very room, pacing up and down between the windows and the door. As I passed in front of a mirror, I saw without surprise that I’d gone grey.

In the morning I was served a plain breakfast at a table in the garden. I’d been there for ten minutes, neither hungry, nor thirsty, nor even thinking, when, coming towards me from the far end of a garden path, almost like something out of a dream, I saw … Concha.

Oh, don’t be surprised! Nothing can be ruled out when talking of her. Her every action is always, without fail, both astounding and vile. As she drew nearer to me, I was anxiously asking myself just what selfish urge could be driving her on – the desire to gaze once more upon her triumph, or the feeling that she might perhaps, by a daring manoeuvre, and to her own advantage, complete my material ruin? Either explanation was equally plausible.

She leaned slightly to one side in order to pass beneath a branch, then folded her parasol and her fan, and sat down in front of me, with her right hand resting on the table.

I remember that behind her there was a flowerbed, with a slender, gleaming spade stuck in the soil. During the long silence that followed, I was possessed by an overwhelming temptation to grab hold of the spade, fling the woman onto the ground, and chop her in two like a common earthworm …

“I came,” she said at last, “to find out how you’d died. I thought that you really loved me, and that you’d have killed yourself during the night.”

Then she poured the chocolate out into an empty cup and raised it to her quivering lips, adding, as if to herself:

“Not cooked enough. It tastes horrible.”

When she’d finished, she stood up, opened her parasol, and said:

“Let’s go inside. I’ve been keeping back a surprise for you.”

“So have I,” I thought.

But I said nothing.

We went up the steps to the verandah. She ran on ahead, singing an aria from a well-known Spanish operetta with a deliberation doubtless intended to make me feel the allusion more keenly:

“And what if I didn’t want you

To go around with your arm in his?

– Then I’d go with him to the fair

And to the bullfight at Carabanchel!”

Of her own accord she went into one of the rooms … I didn’t push her in there, sir … Nor did I wish for what happened next … But such was our common destiny … What had to be, had to be.

The small room she’d entered – I’ll show you it shortly – has carpets hanging everywhere, and is muffled and gloomy like a tomb, with no furniture other than a few couches. I used to go there to smoke. It’s abandoned now.

I followed her in. I closed and locked the door without her hearing. Then the blood – the anger that had been building up inside me day after day for fourteen months – rushed to my head and, turning towards her, I gave her a slap in the face that stunned her.

It was the first time that I’d struck a woman, and it left me as shaken as it did Concha, who’d leapt backwards, seemingly bewildered, her teeth chattering …

“You … Mateo … You did that to me …”

And, amid a violent stream of abuse, she cried out:

“Don’t worry! You shan’t so much as lay another finger on me!”

She was already searching in her garter, where so many women keep a small weapon concealed, when I crushed her hand and threw the dagger up onto a canopy that was almost as high as the ceiling.

Then, holding both her wrists in my left hand, I forced her to her knees.

“Concha,” I said, “I’m going neither to insult you nor to upbraid you. But listen carefully. You’ve made me suffer beyond the limits of human endurance. You’ve devised moral torments in order to inflict them on the only man who’s ever loved you passionately. And I hereby declare that I’m going to have you right now, by force if necessary, and not just once, do you hear, but as many times as I care to before nightfall.”

“Never!” she cried. “I’ll never be yours. I loathe you, I’ve told you so. I hate you! I hate you worse than death itself! So go ahead and murder me then! You shan’t have me any other way!”

It was then that I silently began to hit her … I’d gone completely mad … I don’t really know what happened next … I couldn’t see properly … I couldn’t think straight … All I can remember is that I hit her with the regularity of a peasant wielding a flail – and always on the same two spots: the left shoulder and the top of the head … I’ve never heard such terrible screams …

This went on for perhaps a quarter of an hour. She didn’t say a word, either to beg for mercy or to surrender. I stopped when my fist began to ache, and then I let go of her hands.

She sank down on one side, her arms stretched out in front of her, her head thrown back, her hair dishevelled, and her screams suddenly turned into sobs. She cried like a little child, always at the same pitch, and going for as long as she could without drawing a breath. At times I thought that she was choking. I can still see the movement she incessantly made with her bruised shoulder, and her hands in her hair, removing the pins …

Then I felt so sorry for her, and so ashamed of myself, that for a while I almost forgot the ghastly scene of the night before …

Concha had picked herself up somewhat: she was still kneeling, with her hands up by her cheeks, and her eyes raised towards me … and in those eyes, there no longer seemed to be the slightest hint of reproach, but rather … I don’t quite know how to put it … a kind of adoration … At first her lips were trembling so much that she couldn’t articulate properly … Then I faintly made out:

“Oh, Mateo! How you love me!”

She came closer, still down on her knees, and murmured:

“Forgive me, Mateo! Forgive me! I love you too …”

She was being sincere, for the first time. But I no longer believed her.

“How well you’ve beaten me, my love!” she went on. “How sweet it was! How good … Forgive me for everything that I’ve done to you! I was mad … I didn’t know … Have you really suffered so for me, then? Forgive me, Mateo! Forgive me! Forgive me!”

And she added, in the same gentle voice:

“You shan’t have me by force. I’m ready for you. Help me get up. Did I say that I had a surprise for you? Well, you’ll soon find out what it is: I’m still a virgin. Yesterday’s scene was just play-acting, to make you suffer. For I can tell you now that, until today, I didn’t care for you much. But I’m far too proud to go with someone like Morenito … I’m yours, Mateo. I’ll be your wife this very morning, God willing. Try to forget about the past and to understand my poor little soul instead, for I can’t make head or tail of it. I feel like I’m waking up. I see you as I’ve never seen you before. Come to me.”

And what’s more, sir, she was indeed a virgin …

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

IN WHICH CONCHA CHANGES HER WAY OF LIFE, BUT NOT HER CHARACTER

This would make a good ending to a novel, and with such a conclusion all would be well that ended well! Alas! That I could but stop there! Perhaps you’ll find out for yourself some day that, in the course of a human existence, no misfortune is ever wiped out, no wound ever heals up, and no woman will ever be capable of cultivating happiness in the same devastated field in which she has sown tears and anguish.

Not long after that particular morning – it was a Sunday evening, about a week later – Concha came home a few minutes before dinner, saying:

“Guess who I’ve seen! Someone I’m very fond of … Think now … I was so pleased.”

I remained silent.

“I saw Morenito,” she went on. “He was walking along Las Sierpes, in front of Gasquet’s store. We went to the Cervecería together for a drink. You know, I spoke ill of him to you; but I haven’t told you all that I think. He’s good-looking, is my little friend from Cadiz. But you know that already; you’ve seen him. He has bright eyes with long eyelashes – and how I adore long eyelashes! They give such depth to one’s expression! And then, he doesn’t have a moustache, his mouth is well-formed, his teeth are white … All the women run the tips of their tongues over their lips when they see how nice he is.”

“You’re joking, Conchita … It’s not possible … Tell me now: you didn’t see anyone, did you?”

“Ah! So you don’t believe me then? Just as you please … In that case, I’ll never tell you what happened next.”

“Tell me immediately!” I shouted, grabbing her by the arm.

“Oh! Don’t lose your temper! I’ll tell you! Why should I make a secret of it? I take my pleasure where I find it. We went a little way out of town together, along a little path, so bright, so bright, so bright to the Cruz del Campo. Need I go on? We looked at all the rooms, in order to find the one with the best bed …”

And as I started to my feet, she concluded from behind her protecting hands:

“Come now, it’s only natural. His skin is so soft, and he’s so much better-looking than you are!”

What could I do? I hit her again. Brutally, unsparingly, so that I felt disgusted with myself. She screamed, she sobbed, she prostrated herself in a corner, with her head on her knees, wringing her hands.

And then, as soon as she was able to speak again, she said to me in a tearful voice:

“It wasn’t true, my love … I went to the bullfight … I spent the day there … my ticket’s in my pocket … take it … I was alone with your friend G … and his wife. They spoke to me, they’ll tell you … I saw all six bulls get killed, and I didn’t leave my seat and I came straight home afterwards.”

“But then, why did you say …?”

“So that you’d beat me, Mateo. When I feel your strength, I love you, I really love you – you can’t imagine how happy it makes me to weep because of you. Come here now. Make me well again, quick.”

And that’s how it was, sir, right to the very end. Once she’d become convinced that I was no longer taken in by her false confessions, and that I’d every reason to believe in her fidelity, she invented new pretexts for provoking me to daily outbursts of anger. And in the evening, in those circumstances in which all women repeat: “You’ll always love me, won’t you?”, I had to listen to such astounding but genuine phrases (and I’m not making this up) as: “Mateo, will you beat me again? Promise that you’ll give me a good beating! That you’ll kill me! Tell me that you’ll kill me!”

Don’t go thinking, however, that her character was entirely built around this strange predilection. Oh no! If she felt a need for punishment, she also had a passion for transgression. She did wrong not because sinning gave her pleasure, but because she delighted in hurting people. Her purpose in life was limited to sowing seeds of suffering and watching them grow.

To begin with there were fits of jealousy such as you cannot possibly imagine. She spread such rumours about my friends and about everyone that made up my circle, and if need be showed herself personally so insulting, that I broke with all of them and soon found myself alone. The mere sight of another woman, whoever she might be, was enough to send her into a rage. She dismissed all my female servants, from the poultry girl right up to the cook, although she knew perfectly well that I never even spoke to them. Then, in just the same manner, she drove away those that she herself had chosen. I was forced to change all my suppliers, because the hairdresser’s wife was blonde, because the bookseller’s daughter was dark-haired, and because the woman who sold cigars used to ask for my news when I went into her shop. Before long, I gave up going to the theatre for, indeed, if I looked at the audience, it was to feast my eyes on some woman’s beauty, and if I looked at the stage, it was conclusive proof that I was falling in love with one of the actresses. I stopped going for walks with her in public for the same reasons: the slightest greeting became, in her eyes, a sort of declaration of love. I could neither leaf through a set of engravings, nor read a novel, nor look at an image of the Virgin Mary, lest she accuse me of being infatuated with the model, the heroine, or the Madonna. I always gave in, so greatly did I love her. But after what tiresome fights!

At the same time as I was thus feeling the effects of her jealousy, she was endeavouring to keep mine alive by means that, though contrived to start with, later on became real.

She deceived me. From the care that she took to inform me of the fact, I could tell that she was more interested in arousing my emotions than her own. All the same, even morally speaking, it was hardly a valid excuse; and, in any case, when she got home from these affairs of hers, I was in no fit state to start justifying them, as I’m sure you’ll understand.

Soon it was no longer enough for her to bring me back the proofs of her infidelities. She wanted to repeat the scene at the gate, but this time without any faking. That’s right! She was scheming against herself, in order to be caught in the very act!

It took place one morning. I awoke late. She wasn’t there at my side, but on the table there was a letter, which ran as follows:

‘To Mateo, who no longer loves me! – I got up while you were asleep and I’ve gone to meet my lover at the Hotel X …, room 6. You can kill me there if you wish; the door won’t be locked. I’m going to prolong my night of love until the end of the morning. So come along! If I’m lucky, you might perhaps catch me in a close embrace.

Your adoring,

CONCHA.’

I went there. My God, what a morning that was! A duel followed. It caused a public scandal. You may have heard about it.

And when I think that all this was done to “bind me closer” to her! How women can be blinded by their imaginations when it comes to men’s love!

What I saw in that hotel room lived on thereafter, forming a kind of impenetrable veil between Concha and me. Instead of exciting my desire, as she’d hoped, the memory of it actually seemed to coat and permeate her entire body with something odious, that wouldn’t go away. I took her back, however; but my love for her had suffered a mortal blow. Our quarrels became more frequent, more bitter – more violent as well. She clung to my existence with a kind of frenzy, out of sheer egoism and selfish passion. Her fundamentally evil soul didn’t even suspect that one could love in any other way. She wanted at all costs – whether by fair means or foul – to keep me locked in her embrace. In the end I broke free.

It happened quite suddenly one day, after yet another of our many rows, simply because it was inevitable.

A little gypsy girl, a basket-seller, had come up the garden steps to offer me her humble wares, made of reeds and woven rushes. I was just going to give her some money, out of charity, when I saw Concha rush towards her and tell her, extremely abusively, that she’d already called by the month before, and that she doubtless intended offering me much more than her baskets, adding that one could tell very well from her eyes what her real profession was, that if she walked around barefoot it was to show off her legs and that she must be shameless indeed to go thus from door to door, wearing a petticoat that had obviously got torn while hunting for lovers. All of this was said with the utmost disdain, and peppered with outrageous insults that don’t bear repeating. Then she snatched the girl’s goods from her, broke them all into pieces, and trampled them underfoot. You can just imagine how the poor little thing wept and trembled. I compensated her, of course. Which provoked a battle.

That day’s row was neither fiercer nor more tiresome than any of the others; yet it was final. I still don’t know why. “You’re leaving me for a gypsy!” – “Not at all. I’m leaving you to get some peace.”

Three days later I was in Tangiers. She caught up with me. I left with a caravan for the

interior, where she couldn’t follow me, and for several months I remained without news from Spain.

When I got back to Tangiers, I found fourteen letters waiting for me at the Post Office. I took a steamer to Italy, where I received a further eight letters. Then nothing.

I only returned to Seville after a year spent travelling. She’d got married a fortnight before to some young fool – of noble birth, moreover – that she then lost no time in having sent out to Bolivia. In her last letter to me, she said: “I’ll be yours, and yours alone – otherwise I’ll let whoever wants me, have me.” I imagine that she’s busy keeping the latter promise.

That’s all I had to say, sir. Now you know who Concepción Pérez is.

As for myself: crossing her path has ruined my life. I expect nothing more from her now, except to be forgotten. But such hard-won experience can and should be passed on in the event of danger. Don’t be surprised if I’ve made such a point of talking to you in this way. The Carnival died yesterday; real life begins anew. For your sake I’ve briefly raised the mask of an unknown woman.”

“I’m very grateful,” said André solemnly, shaking him by both hands.

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

WHICH IS THE EPILOGUE AND ALSO THE MORAL OF THIS STORY

André walked back towards town. It was seven o’clock in the evening, and the earth’s metamorphosis was imperceptibly drawing to its close in enchanted moonlight.

To avoid returning the way he had come – or for some altogether different reason – he took the Empalme road, after a long detour across country.

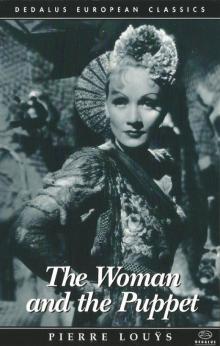

The Woman and the Puppet

The Woman and the Puppet