- Home

- Pierre Louys

The Woman and the Puppet Page 2

The Woman and the Puppet Read online

Page 2

“Doesn’t her husband live in Seville, then?”

“He’s in Bolibie.”

“Where?”

“In Bolibie. It’s somewhere in South America.”

*

Without waiting to hear any more, André tossed another coin into the match-seller’s lap and, merging into the crowd, he headed back towards his hotel.

All in all, he still felt rather undecided. Even with the husband’s absence, about which he had just learnt, he was not convinced that luck was entirely on his side. The reticence of the match-seller, who seemed to know more than he was willing to reveal, suggested that she had already chosen a lover, and the servant’s behaviour was hardly calculated to allay this underlying suspicion. Bearing in mind that scarcely a fortnight remained before the date fixed for his return to France, André wondered whether this would be long enough to enable him to find favour with a young lady whose personal life was doubtless already accounted for.

He was still wrestling with his uncertainty when, just as he was entering the hotel patio, the doorman stopped him, saying:

“I’ve a letter for you, sir.”

There was no address on the envelope.

“Are you sure that this letter is for me?”

“It was handed to me only a moment ago, sir, to be given to Don André Stévenol.”

André opened it without more ado.

It contained a blue card, on which was written the following brief message:

“Don André Stévenol is requested not to make so much noise, not to give his name, and not to ask for mine again. If he goes for a walk along the Empalme road tomorrow afternoon, towards 3 o’clock, a carriage will go by and may, perhaps, pull up.”

“How simple life is!” thought André.

And as he went up the stairs to the first floor, he was already picturing to himself the intimate encounters that lay ahead, and trying to recall the affectionate diminutives of the most charming of all Christian names:

“Concepción, Concha, Conchita, Chita.”

CHAPTER THREE

HOW, AND FOR WHAT REASONS, ANDRÉ DID NOT GO TO CONCHA PÉREZ’S RENDEZVOUS

The following morning was a radiant one. When André awoke, light was streaming in through the four windows of the balcony, and on the white square outside all the sounds of town life – horses’ hooves, hawkers’ cries, bells belonging to mules or to convents – were mingling together in a general animated hum.

He could not recall having had such a joyous start to the day in a long while. He stretched out his arms and tensed them, feeling their strength. Then, as if in anticipation, he clasped them tight to his chest in an illusory embrace.

“How simple life is!” he said again, smiling to himself. “At the same time yesterday, I was alone, aimless and uninspired. All I had to do was go for a stroll, and now here I am, part of a couple! So why do we always expect to be spurned, scorned or even kept waiting? If we just ask, women give themselves. And why should it be otherwise?”

He got out of bed, put on his slippers, wrapped a long cotton loincloth around his waist, and rang for his bath to be prepared. While he was waiting, he pressed his forehead up against the windowpanes, and looked out at the sunlit square.

The houses were painted in those light colours, reminiscent of women’s dresses, with which Seville loves to decorate its walls. Some were cream-coloured, with pure white cornices; some were pink (but of such a delicate shade!); others were orange or sea-green; and others still pale violet. And nowhere were one’s eyes offended by the hideous brown of the streets of Cadiz or Madrid, or dazzled by the glaring whiteness of Jerez.

On the square itself there were orange trees laden with fruit, flowing fountains, and young girls who were laughing as they held the borders of their shawls together in both hands, just like Arab women fastening their loose outer garments. And from all around – from the four corners of the square, the middle of the road, the depths of the narrow alleys – came the tinkling sound of the little bells worn by the mules.

André simply could not imagine how one could live anywhere else but Seville.

After he had finished washing and dressing, and had lingered over a small cup of thick Spanish chocolate, he set out once more, determined to go wherever his feet should happen to take him.

And, strangely enough, it so happened that they took him by the shortest route from the steps of his hotel to the Plaza del Triunfo; but, once there, André recalled the precautions he had been advised to observe and, either because he was afraid of displeasing his “mistress” by passing right in front of her house, or, on the contrary, because he did not wish to appear so tormented by the desire to see her that he could wait no longer, he continued along the opposite pavement without so much as a sideways glance to the left.

From there, he made his way towards las Delicias.

The whole area was strewn with eggshells and bits of paper from the previous day’s battle, which made the magnificent park vaguely resemble a kitchen scullery, and here and there the ground was completely hidden from view beneath what looked like crumbling, variegated dunes. Moreover the place was deserted, for Lent had begun again.

And yet, coming towards him along a path that led in from the countryside, André saw a figure that he recognised.

“Good morning, Don Mateo!” he said, holding out his hand. “I didn’t expect to run into you at this early hour.”

“What else is there to do, sir, when one is alone, idle and useless? I go for a walk in the morning, and again in the evening. During the day I read or go out gambling. That’s the life I’ve chosen to lead, and it’s a gloomy one.”

“But your nights provide some consolation for such days, if I’m to believe local gossip.”

“If they’re still saying that about me, they’re mistaken. You’ll never see another woman at Don Mateo Díaz’s, not from now to his dying day. But don’t let’s talk about me any more. How much longer are you staying here for?”

Don Mateo Díaz was a Spaniard, aged about forty, to whom André had been given a letter of introduction during his first visit to Spain. His gestures and his manner of speech were both naturally rather declamatory and, like many of his fellow countrymen, he was apt to take offence at the most innocent remarks. Not that this implied any conceit or stupidity on his part: the grandiloquence of the Spanish matches their cloaks, which are worn with large, elegant folds in them. Don Mateo was an educated man, and it was only his considerable personal fortune that had prevented him from leading an active life. He was principally known on account of his bedchamber, which had a reputation for hospitality. Consequently André was astonished to learn that he had already renounced the devil and all his wicked pomps and vanities. Nevertheless, the young man refrained from posing any more questions.

For a while they walked along by the Guadalquivir which Don Mateo, being a riverside landowner, and proud of his city, never tired of admiring.

“I’m sure you’ve heard,” he would say, “about the foreign ambassador who joked that he preferred the Manzanares to all other rivers, because it could be navigated both in a carriage and on horseback. But behold the Guadalquivir, father of cities and plains! I’ve travelled widely during the last twenty years, and I’ve seen broader rivers in brighter climes – the Ganges, the Nile, the Atrato – but only here have I seen waters and currents of such majestic beauty. Its colour is incomparable. Doesn’t that look just like spun gold, tapering down to the arches of the bridge? Sometimes the river swells like a pregnant woman, and then the water becomes heavy with soil. It’s all the wealth of Andalusia that passes through Seville’s two wharves, on its way down towards the plains.”

Then they talked politics. Don Mateo was a royalist, and he was outraged by the persistent attacks of the republican opposition at a time when all the country’s forces ought to have been focused around the helpless but courageous queen, in order to help her preserve the supreme heritage of an imperishable past.

“What a d

ecline!” he would say. “What woe! To think that we were once the masters of Europe! We gloried in the might of Charles the Fifth, we doubled the scope of the world’s activities by discovering a new one, we possessed the empire on which the sun never set and, better still, we were the first to defeat your Napoleon – and all this only to perish beneath the cudgels of a handful of mulatto bandits! What a fate for Spain!”

It would never have done to have told him that those same bandits were Washington’s and Bolivar’s brothers. As far as he was concerned, they were shameful brigands who didn’t even deserve to die by the garrotte.

He calmed down, and then continued:

“I love my country. I love its mountains and its plains. I love the people’s language and dress, and the feelings they express. Our race is naturally endowed with superior qualities. It constitutes an aristocracy in its own right, standing aloof from the rest of Europe, interested only in itself, and remaining shut away on its estates as if within a walled garden. That no doubt explains why it’s in decline – and to the benefit of the Northern nations, in accordance with that contemporary law which seems to impel the mediocre everywhere to attack all that is finest. In Spain, you know, the descendants of families that have no trace of Moorish blood in their veins are considered members of the nobility. We’re unwilling to admit that, for seven hundred years, Islam took root in Spanish soil. Personally, however, I’ve always thought that to disown such ancestors was to display great ingratitude. To whom, if not to the Arabs, do we owe those outstanding qualities that have enabled us to stamp the pages of history with the mighty portrait of our past achievements? They’ve bequeathed to us their contempt for money, falsehood and death, as well as their inexpressible pride. Our exceptionally upright attitude when confronted with all that is base comes from them, as does a certain indefinable indolence with regard to manual work. In truth, we are their children, and it’s not without reason that we continue, to this day, to perform their Oriental dances to the sound of their ‘fierce ballads’.”

The sun rose higher in the broad expanse of clear, blue sky. The old trees that stood like masts in the park were still brown, although in places the green of laurels and supple palms could be seen peeping through. Sudden blasts of hot air cast their spell over this winter’s morning, in a land where winter never lingers.

*

“You’ll come and have lunch with me, I hope,” said Don Mateo. “My estate lies over that way, near the Empalme road. We can be there in half an hour and, if you have no objection, I’ll detain you till evening, in order to show you my stud farm, where I’ve some new animals.”

“You’ll think me terribly rude,” apologised André. “I accept the invitation to lunch, but not the excursion. I’ve a rendezvous later this afternoon that I really must keep.”

“With a woman? Have no fear, I won’t ask questions. Go right ahead. In fact, I’m grateful to you for spending with me such time as remains before the appointed hour. When I was your age, such days were filled with mystery and I couldn’t bear to see anyone at all. I’d have my meals brought to me in my room, and the woman I was waiting for would be the first person I had spoken to since waking up that morning.”

He fell silent for a moment, and then, as if by way of advice, he added:

“Ah! Beware of women, sir! I’m not suggesting that you shun them altogether, for I’ve worn my life out in their company, and if I had to begin it all over again, the hours so spent would be among those I’d wish to relive. All the same – be careful, be very careful where they’re concerned!”

Then, as if he had hit upon an expression that neatly summed up his thoughts on the matter, Don Mateo slowly added:

*

“There are two kinds of women that should be avoided at all costs: firstly, those that do not love you; and secondly, those that do. Between these two extremes there are thousands of delightful women – only we don’t know how to appreciate them.”

Lunch would have been a rather dull affair had Don Mateo, who was in good form, not livened it up with a long monologue that helped make up for the conversation that was otherwise lacking; for André, engrossed in his own private thoughts, was only half-listening to what was being said to him. As the moment of his rendezvous drew nearer, so his heartbeat quickened, and the palpitation that he had first felt stirring inside him the day before grew ever more insistent. It was like a deafening summons from within himself, an imperious command that banished from his thoughts everything but the woman he was waiting for. He would have given anything for the little hand of the Empire clock on which his gaze was fixed to have been moved forward by fifty minutes. But time seems to stand still when one keeps looking at the clock, and now it slipped by no faster than the water in an eternally stagnant pond.

At length, obliged to remain, and yet unable to keep quiet a moment longer, he betrayed something of his relative youth by addressing his host in the following unexpected terms:

“Don Mateo, you’ve always given me excellent advice. Would you mind if I told you a secret, and then asked for your opinion?”

“I’m entirely at your disposal,” said Don Mateo, with typical Spanish courtesy, as he rose from the table in order to go through into the smoking room.

“Er … well now …” André stammered, “it concerns … Really, I wouldn’t broach the subject with anyone else, but … Do you happen to know anyone in Seville called Doña Concepción García?”

Mateo gave a start.

“Concepción García! Concepción García! But which one? Explain yourself! There are thousands of Concepción García’s in Spain! It’s as common a name here as Jeanne Duval or Marie Lambert in your own country. For God’s sake, tell me her maiden name. Tell me now, is it P … Pérez? Is it Pérez? Concha Pérez? Well say something then!”

André was completely taken aback by this sudden display of emotion, and he had a fleeting premonition that it would be better not to tell the truth; but before he could stop himself he blurted out, rather sharply:

“Yes.”

Then, emphasising each detail as if probing at a wound, Mateo continued:

“Concepción Pérez de García, 22 Plaza del Triunfo, eighteen years old, hair nearly black, and lips … lips …”

“Yes,” said André.

“Ah! You’ve done the right thing in asking me about her. You’ve done the right thing, sir. If I can stop you from crossing that woman’s threshold, that’ll be a good deed on my part, and a rare stroke of luck for you.”

“But who is she?”

“What! You mean you don’t know her?”

“I met her for the first time yesterday, and I haven’t even heard her speak yet.”

“In that case, it’s not too late!”

“She’s a harlot?”

“No, no. All things considered, she’s actually rather respectable. She hasn’t had more than four or five lovers, and in this day and age, that’s chaste indeed.”

“And …”

“Furthermore, she’s remarkably intelligent. Remarkably so. Take my word for it. I consider her to be without equal, both for her shrewd mind and for her intimate knowledge of life. I’ll give the woman her due. She displays the same irresistible eloquence when she dances as when she speaks, when she speaks as when she sings. That she has a pretty face – well, I expect you know that already; and if you were to see the rest of her, you’d say that even her lips … But that’s enough of all that. Have I left anything out?”

Irritated, André did not reply.

Then Don Mateo seized hold of the sleeves of his jacket and, accentuating each and every word with a tug, he added:

“And she’s the WORST of women, sir. Do you hear me, sir? She’s the WORST woman in the whole wide world. My only consolation now is the heart-felt hope that, the day she dies, God will not forgive her.”

André stood up.

“Nevertheless, Don Mateo,” he said, “as yet I’m not entitled to speak of this woman as you do, and I’ve no rig

ht not to go to the rendezvous that she’s given me. I need hardly remind you that what I’ve told you is a secret, and I regret now having to interrupt yours by an early departure.”

And he held out his hand.

Mateo, however, went and stood in front of the door.

“Listen to me, I beseech you. Just listen to me. Only a moment ago you were saying that I could always be relied upon to give excellent advice. I don’t agree with you there; nor do I require any such praise in order to speak to you in this way. And leaving aside also the affection I have for you, and which would, moreover, be quite enough in itself to account for my insistence …”

“Well, what is it?”

“I’m going to speak to you man to man, just as someone might stop a passer-by in the street to warn him of some serious danger; and so let me cry out to you: Stop right there! Turn back, and forget all about whoever you’ve seen, whoever’s spoken to you, whoever’s written to you! If you already enjoy peace, calm nights, a carefree life, and everything else that goes by the name of happiness – keep away from Concha Pérez! Unless you want to see this very day divide your past from your future in two halves of joy and anguish – keep away from Concha Pérez! If you haven’t yet experienced to the utmost degree the folly that she can engender and maintain in a man’s heart – keep away from that woman, flee her as you would death itself, and let me save you from her! In short, take pity on yourself!”

“Do you love her then, Don Mateo?”

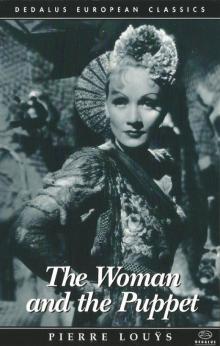

The Woman and the Puppet

The Woman and the Puppet