- Home

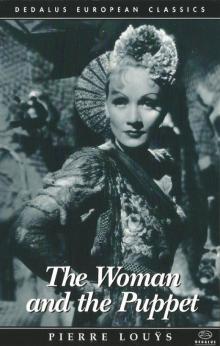

- Pierre Louys

The Woman and the Puppet Page 3

The Woman and the Puppet Read online

Page 3

The Spaniard put his hand to his forehead and murmured:

“Oh! that’s over and done with now. I no longer either love her or hate her. It’s all in the past. Everything fades away in the end …”

“In that case, perhaps you won’t take it personally if I refrain from following your advice? I’d willingly make such a sacrifice for your sake, but there’s no need for me to do so for my own … What do you say?”

Mateo looked at André; then suddenly changing the expression on his face, he facetiously replied:

“My dear sir, one should never go to the first rendezvous that a woman gives to one.”

“And why’s that?”

“Because she won’t show up.”

This witticism brought back a particular memory for André, and he could not help smiling.

“That’s sometimes true,” he admitted.

“Frequently. And if by any chance she were waiting for you at this very moment, you can be quite certain that your absence would only ensure her inclination for you.”

*

André thought this over for a moment, and then smiled again.

“Which means …?”

“… Which means that leaving personal considerations aside, and even supposing that the woman you’re interested in were called Lola Vásquez or Rosario Lucena, I’d advise you to return to the armchair in which you were seated a moment ago, and not to leave it again without very good reason. We’re going to smoke a cigar or two whilst enjoying an iced fruit cordial. It’s a combination rarely found in the restaurants of Paris, but it’s common enough throughout Latin America. In a moment you must tell me whether you’re enjoying to the full the blend of Havana smoke and cool sugar.”

A short silence ensued. They had both sat down on either side of a small table, on top of which were cigars and circular ashtrays.

“Well now, and what shall we talk about?” enquired Don Mateo.

André just gestured, as if to say: You know perfectly well.

“I’ll begin then,” continued Mateo, lowering his voice; and the assumed cheerfulness he had momentarily displayed vanished as a lasting cloud of gloom settled over his features.

CHAPTER FOUR

APPARITION OF A LITTLE MOORISH GIRL IN A POLAR LANDSCAPE

Three years ago, sir, I didn’t have these grey hairs that you can see now. I was thirty-seven years old, but I thought I was still twenty-two. Never, at any moment in my life, had I been aware that my youth was slipping away, nor had anyone yet made me understand that it was coming to an end.

You’ve been told that I was a womaniser. It’s not true. I’ve always had too great a respect for love to ever wish to frequent the back rooms of certain establishments, and I’ve hardly ever possessed a woman with whom I wasn’t passionately in love. If I were to run through their names for you, you’d be surprised how few of them there are. Only recently, while doing this simple sum in my head, it struck me that I’d never had a blonde mistress. I’ll never have known those pale objects of desire.

What is true, however, is that for me love has never been simply a distraction or a pleasure – a mere pastime, as it is for some. It’s been the very essence of my life. If I were to erase from my memory all the thoughts and deeds that have revolved around women, there’d be nothing left, only emptiness.

Now that has been said, I can tell you what I know about Concha Pérez.

*

Three years ago – three and a half, to be exact – I was returning from France in the express train that crosses the bridge at Bidasoa towards noon. It was 26th December, and bitterly cold. The snow, already extremely heavy over Biarritz and San Sebastián, had made the route through Guizpúzcoa practically impassable. The train had to wait for two hours at Zumárraga whilst workmen hurriedly cleared the track; then we set off once more, only to stop again, this time in the middle of the mountains, and it took three hours to repair the damage caused by an avalanche. All night long, it was the same thing. The carriage windows, thickly coated in snow, deadened the noise of our journey, and the danger lent a certain grandeur to the silence through which we were travelling.

Next morning we drew up outside Avila. The train was running eight hours late, and we hadn’t eaten anything for a whole day. When I asked a railway employee whether we could get out, he shouted back:

“Four day’s halt. The trains can’t get through.”

Do you know Avila? It’s the place to send anyone who thinks that the old Spain is dead. I had my bags carried to an inn, such as Don Quixote might have stayed at. There were fringed leather trousers stretched out over the fountains and in the evening, when shouting in the streets outside informed us that the train was suddenly leaving again, the stagecoach drawn by black mules that swept us off at a gallop through the snow, all but overturning a dozen times, was undoubtedly the very same one that long ago used to convey King Philip the Fifth’s subjects from Burgos to the Escorial.

What I’ve just described to you in the space of a few minutes, sir, actually lasted forty hours.

And so when, towards 8 o’clock at night, in the middle of winter, and deprived of my dinner for the second day running, I resumed my corner-seat in the rear of the train, it’s hardly surprising that I found myself suddenly overcome by the most terrible feeling of irritation. I simply didn’t feel up to spending a third night in the same carriage as the four sleeping Englishmen who’d been with me since Paris. I left my bag in the luggage rack and, taking my blanket with me, I settled down as best I could in a third class compartment, which was full of Spanish women.

In fact, I should really have said four compartments, not one, for the partitions between each section weren’t much higher than the seats themselves. In them there were a number of working class women, a few sailors, a couple of nuns, three students, a gypsy and a Civil Guardsman. It was a mixed crowd, as you can see, and they all spoke at once, in extremely shrill voices. I’d hardly been sitting there for more than a quarter of an hour, and yet I already knew the life story of everyone around me. Some people make fun of those who confide in others in this way, but personally I can never observe without being moved to pity this need that simple folk have to cry out their sorrows in the wilderness.

All of a sudden the train stopped. We were crossing the Sierra de Guadarrama, at an altitude of 1400m., and a fresh avalanche had just barred our way forward. The train tried to back up, but another one was blocking our retreat. And the snow kept on falling, gradually burying the carriages.

It sounds more like an account of Norway that I’m giving you doesn’t it? If we’d been in a Protestant country, everyone would have gone down on their knees, commending their soul to God; but, except when it thunders, we Spanish don’t fear any sudden retribution from on high. On learning that the train was quite definitely trapped, everyone turned to the gypsy, and asked her to dance.

And dance she did. She was about thirty years old and, like most women of her race, extremely ugly; but from her waist down to her calves, she seemed to be on fire. In no time at all the snow, the cold, and the darkness outside were forgotten. The passengers in the other compartments were kneeling on the wooden benches and, with their chins resting on the partitions, they too were watching the gypsy. Those nearest to her struck the palms of their hands in time to the changing rhythms of her flamenco dance.

It was then that I noticed, in the corner opposite me, a little girl who was singing.

She was wearing a pink petticoat, which told me straightaway that she was from Andalusia, for Castillians prefer darker colours, such as the black worn by the French, or the brown favoured by the Germans. Her shoulders and nascent bosom were hidden beneath a cream-coloured shawl, and to protect herself against the cold, she’d wrapped around her head a white scarf, whose ends hung down behind her in two long points.

As everyone else in the carriage already knew, she was a pupil at the Convent of San José in Avila who was on her way to Madrid to meet her mother. I also learnt that she di

dn’t have a fiancé, and that her name was Concha Pérez.

Her voice was unusually piercing. She sang without moving, lying almost stretched out with her hands under her shawl and her eyes closed; but I don’t think that it was the nuns who’d taught her what she was singing. She chose well from amongst those four line folk songs into which the common people put all their passion. I can still hear the way her voice seemed to caress you when she sang:

“Tell me, my girl, if you love me;

Open up to me now, and let’s see …”

or:

“Thy couch is of jasmine,

With white roses for sheets,

Thy pillows are lilies –

And now, sweet rose, sleep.”

Those are just some of the milder ones.

Suddenly, however, as if she’d sensed the absurdity of addressing such hyperboles to that savage creature, the style of her repertoire changed, and from then on she only accompanied the dancing with ironic songs such as this one, which I can still remember:

“Little girl with twenty lovers

(And with me that’s twenty-one),

If they’re anything like I am,

You’ll end up all alone.”

At first the gypsy didn’t know whether to laugh or get angry. The other passengers, who were all laughing, had been won over by the young singer, and it was quite obvious that this particular “daughter of Egypt” didn’t count among her accomplishments that readiness of wit which, in our modern societies, is replacing a readiness with one’s fists as the best way to settle an argument.

She remained silent, gritting her teeth. Meanwhile the little girl, quite reassured now as to the outcome of her skirmish, became more impudent and high-spirited than ever.

She was interrupted by a furious outburst from the gypsy, who was raising her two clenched hands in the air:

“I’ll scratch your eyes out! I’ll scratch your …”

“I’d better watch out then!” replied Concha, as coolly as you please, without even raising an eyelid. Then, amidst a torrent of abuse, she added in the same calm voice, and just as if she had a bull in front of her:

“Guards! Fetch me a couple of assistants!”

Everyone in the carriage was delighted. ¡Olé! went the men, whilst the women all looked at her with good-natured affection.

Only once did she become flustered, and that was in response to an insult that obviously touched a nerve: the gypsy called her “a mere chit of a girl”.

“I’m a woman,” she cried, striking her tiny budding breasts.

And, with genuine tears of rage, the two combatants flung themselves at each other.

I intervened. I’ve never been able to watch women fighting with the same detachment that the common herd usually displays in front of such a spectacle. Women fight badly and dangerously. They’re not familiar with the punch that can knock an opponent down; they only know how to scratch with their nails, which disfigures, or stab with a needle, which blinds. They frighten me.

I separated them, then, and it wasn’t easy. None but a fool would come between two warring women! I did my best, however; after which, stamping their feet on the ground with suppressed fury, they sank back into their respective corners.

When everything had quietened down, a great big lanky fellow, wearing the uniform of a Civil Guardsman, suddenly appeared from an adjoining compartment. With his long, booted legs he stepped over the wooden partition that also forms the back of the seats, ran his eyes protectively over the battlefield, where there was nothing more to be done, and, unerringly going for the weakest person present, as the police invariably do, he gave poor little Concha a stupid, brutal slap in the face.

Without deigning to explain this summary verdict, he made the child move into another compartment, then returned to his own with another great stride of his ridiculous boots, and solemnly folded his hands over his sword, with all the satisfaction of one who has just restored law and order.

The train had started up again by now. The scenery as we went past Santa Maria de las Nieves was incredible. An immense bowl-shaped hollow, almost entirely coated in whiteness, and bounded on the horizon by a pale mountain range, lay stretched out beneath a thousand-foot precipice. The very soul of this snow-covered sierra was clearly the brilliant, icy moon, and nowhere have I seen it more divine than there, on that winter’s night. The sky was pitch black; the moon alone shone, along with the snow. At times, I had the impression that I was in a silent, fantastical train, on a voyage of polar discovery.

I was the only person to see this mirage. My fellow-passengers were all sound asleep. Have you ever noticed, my dear friend, how people never look at the things that are really worth seeing? Last year, for instance, as I was crossing Triana Bridge, I stopped to admire the most beautiful sunset of the year. Nothing can give you any idea of the splendour of Seville at such a moment. Well, then I looked at the passers-by. They were all going about their business, or chatting away as they strolled about, unable to escape their boredom; but not one of them turned round. That magnificent evening spectacle – no-one saw it.

As I gazed at the snow-filled, moonlit night, my eyes already growing tired of the dazzling whiteness, the image of the little girl who’d been singing flashed through my mind, and this juxtaposition of the young Moorish girl and the Scandinavian landscape made me smile. It was something droll and illogical, like a tangerine on an ice floe, or a banana at the feet of a polar bear.

Where was she? I leant over the top of the partition and I saw that she was right by me, so close that I could almost touch her.

She’d gone to sleep with her mouth open and her arms folded beneath her shawl, and her head had slipped down so that it was resting on the arm of the nun beside her. I was quite willing to believe that she was a woman, as she’d told us so herself; but she slept, sir, like a six-month-old child. Her face was almost entirely muffled up in her tasselled headscarf, which hugged the rounded outline of her cheeks. A black ringlet of hair, a closed eyelid above long lashes, a small nose that caught the light and a pair of lips half-hidden in shadow – that’s all that I could see of it, and yet I lingered till dawn over that singular mouth of hers, at once so childlike and so sensual that at times I wasn’t sure whether the movements it made as she dreamt sought the wet nurse’s nipple or a lover’s lips.

Day broke as we were going past the Escorial. As far as the eye could see the wonders of the sierra had given way to the dull, dry winter of the suburbs. Shortly afterwards, we drew into the station and, as I was getting my case down, I heard a little voice outside crying:

“Look! Look!”

She was already out on the platform, pointing at the mounds of snow which, from one end of the train to the other, covered the carriage roofs, stuck to the windows, and capped the buffers, the springs and the ironwork; and the pitiful appearance of our train when compared with the perfectly spotless ones that were waiting to leave the city was making her roar with laughter.

I helped her gather her bundles together, and I wanted to get someone to carry them for her, but she refused. There were six of them in all, and she swiftly got hold of their handles as well as she could, slipping one over her shoulder, dangling a second from her elbow, and taking the other four in her hands. Then off she ran.

And I lost sight of her.

You can see just how vague and insignificant this first encounter was, sir. It’s no opening to a novel: more space is devoted to the setting than to the heroine, and I could have left her out altogether. But what could be more unpredictable than a love affair in real life? And that’s truly how this one began.

Even today I’d swear that, if someone had asked me that same morning what had been the high point of the night for me, what memory I’d have later of those particular forty hours out of so many thousands of others, I’d have talked about the scenery, and not about Concha Pérez.

She’d kept me amused for twenty minutes or so. Her little image cropped up in my thoughts once o

r twice more, but then, having other business to attend to elsewhere, I moved on and soon forgot all about her.

CHAPTER FIVE

IN WHICH THE SAME PERSON REAPPEARS IN A MORE FAMILIAR SETTING

The following summer, I suddenly met her again.

I’d been back in Seville for quite some time, long enough to have picked up once more with an old flame, and then to have broken it off again.

But I’m not going to tell you about that. You’re not here to listen to my life story; besides, I take little pleasure in confiding memories of a private nature. But for the strange coincidence that brings us together over a woman, I’d never have revealed this fragment of my past to you. Let’s hope that even between the two of us this disclosure will remain an exception.

In August, for the first time in years, I found myself all alone in a house that had always been filled with a woman’s presence. The second place-setting at the dinner table removed, no dresses in the wardrobes, an empty bed, silence everywhere … If you’ve ever been a lover, you’ll know what I mean and how horrible it is.

To escape the anguish of this loss, which was worse than any bereavement, I stayed out from dawn till dusk, wandering around aimlessly, on horseback or on foot, with a shotgun, or a walking stick, or else a book; sometimes I even slept at an inn so as not to have to go back home. One afternoon, for want of anything better to do, I went into the tobacco factory in Seville – the Fábrica.

It was a sweltering hot summer’s day. I’d lunched at the Hotel de París, and afterwards, while getting from Las Sierpes to the calle San Fernando, “at the time of day that sees only dogs and Frenchmen in the streets”, I thought that the sun would finish me off.

I went in, then, and I went in alone, which is a special favour for, as you know, visitors are usually shown around this immense harem of four thousand eight hundred women (who are as free in their dress as in their speech) by a female supervisor.

The Woman and the Puppet

The Woman and the Puppet